Come October in Chicago, the spires of the Sears Tower glow pink against the night skyline. NFL players sport shocking pink chin straps and shoe covers. And since 1991, the color pink in a multitude of forms has been used to signify awareness that an estimated 230,480 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in women in 2011.

Breast cancer is not the most deadly of diseases that women face. More women die from lung cancer, and heart disease remains the number one killer. Breast cancer, however, has ignited in our popular culture a fervor to grow awareness and attention that far surpasses more statistically significant illnesses. Breasts – in both their physical and symbolic form – signify nourishment and sustenance as well as feminine beauty and sexuality, attributes that are elementally compelling.

The fact that companies and individuals have been swept up in a sea of pink in support of safeguarding the lives of wives, mothers, and daughters – and by extension – the cultural embodiment of nourishment, feminine beauty and sexuality – is not surprising. What is surprising is that despite the fervent support of millions of individuals and millions of dollars is that the incidence of breast cancer in developing countries remains alarmingly high, and women who are diagnosed with the disease continue to endure significant hardships as a result of conventional medical management for the disease, with slim to negligible gains in terms of survival rates.

Breast Cancer Survival Statistics

A Voice of Integrity

In a seminal 2001 essay, “Welcome to Cancerland” (Harper’s Magazine November, 2001), journalist and activist Barbara Ehrenreich expounds on her thoughts, feelings and research inquiries preceding and surrounding her diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Engaging and punctuated with her signature wry humor, Ehrenreich recounts the initial anxiety, fear, and confusion in the aftermath of her biopsy followed by frank rejection and anger towards what she terms a breast cancer “cult” or “given [the] more than two million women, their families, and friends – ….a full-fledged religion.”

Ehrenreich acknowledges that some progress and certain strides have been made in terms of cultural acceptance of breast cancer as a disease. Gone are the days when “breast cancer was a dread secret, endured in silence and euphemized in obituaries as a ‘long illness.” Likewise a thing of the past is the grievous miscarriage of informed patient consent, “common in the seventies, of proceeding directly from biopsy to mastectomy without ever rousing the patient from anesthesia.”

Ehrenreich nevertheless expresses justifiable outrage at the inundation of “teddy bears [and] pink-ribbon brooches [that] serve as amulets and talismans, comforting the sufferer and providing visible evidence of faith” to the followers of the breast cancer cult. Her outrage springs not necessarily from the promotional efforts made by breast cancer awareness groups, but the fact that these “talismans of faith” are promoted in lieu of meaningful strides in reduction of breast-cancer-inducing environmental toxins or promotion of breast-saving healthful treatment modalities. “In the harshest judgement,” she proclaims, “the breast cancer cult serves as an accomplice in global poisoning – normalizing cancer, prettying it up, even presenting it, perversely, as a positive and enviable experience.”

In the name of advocacy, breast cancer groups have courted corporate sponsorship and have seriously compromised the integrity and usefulness of their message, as measured in a reduction in the incidence of breast cancer and an increase in the rate of survival. Of particular concern, breast cancer advocacy and awareness efforts on behalf of corporate sponsors have lead to a number of constraining and limiting beliefs and attitudes that some writers claim hinder and obfuscate the path to a world without breast cancer.

Infantilization to Exhort Obedience

Ehrenreich found not comfort, but a sense of questioning alarm that anyone would think to present an adult woman with cosmetics, teddy bears, and crayons upon receiving a diagnosis of a life-threatening disease. She muses, “Possibly the idea is that regression to a childlike state of dependency puts one in the best frame of mind with which to endure the prolonged and toxic treatments.” Of note, such “infantilization” as Ehrenreich terms it, does not have its counterpart in the support of men who receive a diagnosis of cancer. She points out that “men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not receive gifts of matchbox cars.” Ehrenreich suggests that this infantilization through the gifting of bears, crayons, and the like could be an insidious means of lulling women into a blind, unquestioning obedience. A slavish dependency on treatment modalities that given different circumstances, they would never consent to willingly.

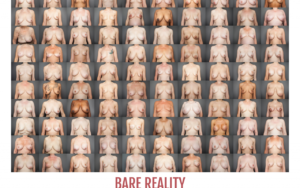

Just as limiting and diversionary as the association of breast cancer with infantile products such as teddy bears are the efforts to “pretty-up,” feminize, and even sexualize the damage and hardships women incur as a result of conventional medical management and the disease itself. In the November 14, 2010 issue of the New York Times Magazine, writer and editor Peggy Orenstein poses the question, “What message are girls really getting from breast-cancer activism?” Many young girls are encouraged and readily participate in the promotion of “pink” products; rubber bracelets sporting the phrase, “I (heart) boobies,” and a slew of t-shirts with adolescent appealing irreverencies such as, “‘Save the Ta-Tas’ and ‘Save Second Base.’” Orenstein laments that “today’s fetishizing of breasts comes at the expense of the bodies, hearts, and minds attached to them,” and might not be the best context in which to frame breast health awareness for young women or our culture at large. Orenstein puts it, “sexy cancer supresses discussion of real cancer, rendering its sufferers – the ones whom all this is supposed to be for – invisible.”

The reality is that dying from breast cancer is not pretty and not sexy. In a 1980 study of 166 women with breast cancer who were autopsied following their death, 26% were reported as having died of pulmonary insufficiency. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7388758) Basically, these women had suffocated to death because their lung tissue had converted to tumor as their disease progressed beyond control. 14% died as a result of hepatic insufficiency, meaning their livers were no longer carrying out the functions necessary to life, once again because their livers had become mostly cancerous tissue. External symptoms of hepatic insufficiency include, but are not limited to: coated tongue, itchy skin, excessive sweating, offensive body odor, dark circles under the eyes, red swollen and itchy eyes, acne rosacea, brownish spots and blemishes on the skin, flushed facial appearance or excessive facial blood vessels. Other symptoms include jaundice, dark urine, pale stool, bone loss, easy bleeding, itching, small, spider-like blood vessels visible in the skin, enlarged spleen, fluid in the abdominal cavity, chills, pain from the biliary tract or pancreas, and an enlarged gallbladder.

While the conclusion of the study is more indicative of the personal bias’ of the researchers and publisher (the conclusion seeks to downplay the dangers of chemotherapy and the publisher is the American Cancer Society) the more significant and lasting impression created by the study is in the details. The authors describe the findings of the autopsies in impersonal, anatomical terms. However, removed from the clinical descriptions, a story of how each woman died can be inferred. A story of gradual degeneration and loss of bodily function accompanied by fear, pain, anger, depression, loneliness, and perhaps in the end, acknowledgement of the inevitable. The act of reducing breast cancer awareness to a prettily-colored product or a witty quip can provide welcome relief from what Orenstein terms, “combat fatigue,” a respite from the very real and grim realities that we all would rather not face on a day-to-day basis. At the same time, such an act of reduction and denial, “discourages understanding, undermin[es] the search for better detection, safer treatments, causes and cures.” The 166 women who participated in the Cancer study each chose to donate her body to science so that some enlightenment and good might come from her personal experience. Such acts must be given their due.

Pacification of Righteous Anger

One of Ehrenreich’s overriding contentions with mainstream breast cancer culture is that there is no room made for anger, dissent, or any attitude or emotional nuance other than “relentless brightsiding.” Women are expected to be accepting of their diagnosis, thankful for the treatments, and forever grateful that they passed the transformative initiation rites into survivorhood. Nevermind, as Ehrenreich posted to a Komen.org message board, the “debilitating treatments, recalcitrant insurance companies, environmental carcinogens, and…’sappy pink ribbons.’ The collective response or “chorus of rebukes” from fellow “survivors” cited a lack of appreciation for her “bad attitude” and the suggestion that Ehrenreich, “run, not walk to some counseling.” What is it about mainstream breast cancer culture that seeks to pacify righteous anger and smooth over dissent from the established norm?

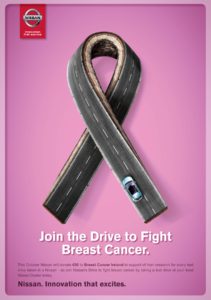

In recently published works, authors Gayle A. Sulik and Samantha King both explore in-depth the well-oiled machinery of a lucrative market-driven philanthropic industry that has grown up around breast cancer. The very sincere hope within our culture that a “cure” will be found within our lifetimes is exploited by for-profit corporations that have readily jumped on the philanthropic bandwagon of “cause-related” marketing. Barbara Brenner, former executive director of the non-profit Breast Cancer Action comments on King’s work, Pink Ribbon, Inc, “Breast cancer advocacy is being transformed from meaningful civic participation into purchasing products.” Righteous anger and dissent do not sell cars, yogurt, cosmetics, or fried chicken.

Meaningful Action

Spearheaded largely through the efforts of San Francisco based non-profit Breast Cancer Action (BCA) (http://bcaction.org) organized pressure has been applied to create meaningful action within the breast-cancer-awareness philanthropic community. Termed “Think Before You Pink” Breast Cancer Action calls attention to “pinkwashing” or the marketing strategy employed by companies such as Yoplait, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Avon that identify themselves publicly as participants in breast cancer awareness campaigns, while manufacturing and marketing products that might contribute to the incidence of the disease.

In 2010, Kentucky Fried Chicken publicly partnered with Susan G. Komen, ostensibly to promote breast cancer awareness by packaging and selling their product in the signature KFC bucket done up in pink. Researcher and scientific advisory Board member of both Susan G. Komen and Breast Cancer Action, Ralph Moss, PhD commented on the unwholesome alliance, “At a time when healthy eating is under broad attack, Komen has chosen to associate itself with products that may, ironically, be linked to an increased incidence of breast cancer, especially in poor and minority communities.”

In 2010, Kentucky Fried Chicken publicly partnered with Susan G. Komen, ostensibly to promote breast cancer awareness by packaging and selling their product in the signature KFC bucket done up in pink. Researcher and scientific advisory Board member of both Susan G. Komen and Breast Cancer Action, Ralph Moss, PhD commented on the unwholesome alliance, “At a time when healthy eating is under broad attack, Komen has chosen to associate itself with products that may, ironically, be linked to an increased incidence of breast cancer, especially in poor and minority communities.”

In 2008, Yoplait yogurt marketed pink-topped individual-sized yogurts made with milk from cows treated with rBGH (recombinant bovine growth hormone developed by Monsanto to increase milk production in dairy cattle and now produced by Eli Lilly, a company that also manufactures cancer treatment drugs). The link between consuming rBGH and the incidence of breast, colon and prostate cancers is compelling: https://thinkbeforeyoupink.org/past-campaigns/about/dairy-breast-cancer/

Public pressure applied through the efforts of Breast Cancer Action’s Put a Lid on It campaign led Yoplait manufacturer General Mills to repeal the use of rBGH produced milk from their products.

Cosmetic manufacturer Avon heavily promotes their Walk for Breast Cancer and contradictorily sells products to women that contain known and “hidden” carcinogens.

Contextualizing Awareness

While the actions and fund garnering policies of the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation and the Avon Foundation for Women can be viewed as contradictory and hypocritical, some efforts have been made to advance science and research that might eventually lead to a meaningful reduction in the incidence of breast cancer. Susan G. Komen for the Cure commissioned a scientific review of environmental factors and the incidence of breast cancer. The review was conducted by the Silent Spring Institute and sought to report on “modifiable influences on breast cancer.” The results of the compilation are available here:

Still, if you want to see charitable contributions and efforts go towards meaningful strides in reducing the incidence and increasing the chances of survival of people diagnosed with breast cancer, consider supporting the following organizations:

To learn more about the complexities around corporate breast cancer philanthropy:

Sulik, G. A. (2012). Pink ribbon blues. Oxford University Press.